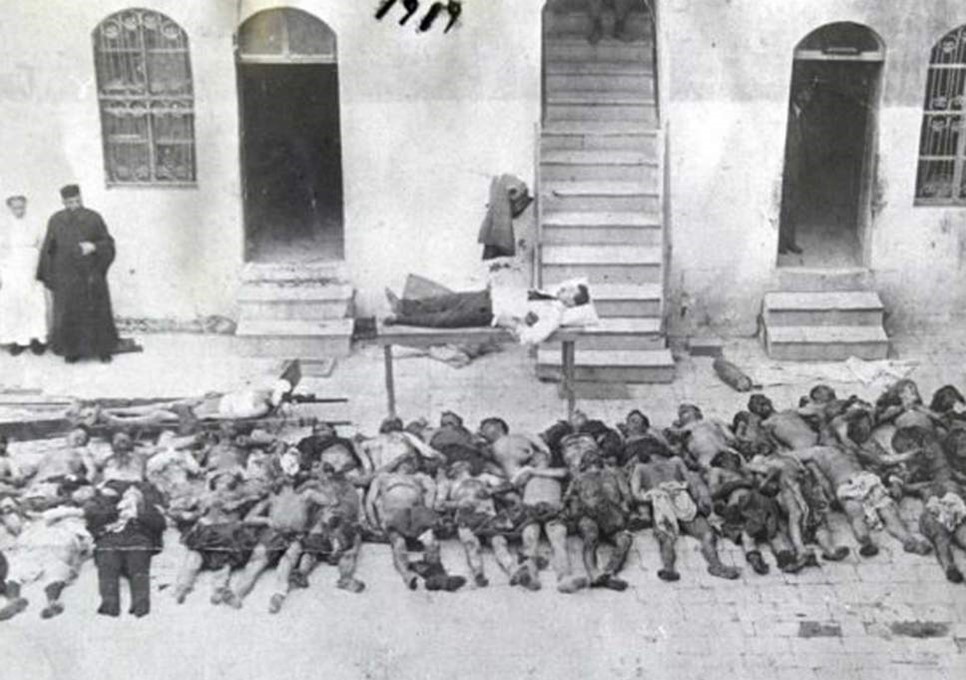

Paul Vangelisti in Modena (photo by David Garyan)

Paul Vangelisti in Modena (photo by David Garyan)

November 13th, 2023

Interlitq’s Californian Poets Interview Series:

Paul Vangelisti, Poet, Translator, Editor, Journalist

interviewed by David Garyan

This interview was conducted in person at the Best Western Hotel Liberta in Modena, Italy on July 3rd, 2022. Bill Mohr contributed four questions via email, which were asked during the course of the talk. The following is the transcription, edited in collaboration with Paul Vangelisti.

Paul Vangelisti’s poems appear in Interlitq’s California Poets Feature

DG: Ezra Pound believed that poets make the biggest leaps in their own craft by translating other poets. As an Italian-American, how have your translations—varied throughout the years—contributed to the development of your own writing?

PV: I started with Pound on this question in 1968 during my first year in graduate school, which I loathed and quit almost after two weeks. But then I had my first class with a visiting professor—Donald Davie. He was there at USC from 1968 to 1969, on his way the next year to accept a chair at Stanford. He was a very fine British poet-critic and he taught one course each semester on Pound. I had read Pound’s Selected Poems right after I graduated from the University of San Francisco. It so happened that the next semester he no longer wanted to teach it. Instead, he ended up with one course I had never taken in my life—creative writing. He had set it up to function as follows: He picked seven people. Grads and undergrads turned in a manuscript. He didn’t distinguish. And the only requirement was that you had to translate something. He met with you the first week to talk about your interests and to find out if you had studied another language. He would suggest a poet to translate in a bilingual format. The other requirement was that you’d never meet any of the other poets. It was one-on-one with him. It was the shrink’s hour—fifty minutes, once a week. It was whatever he wanted to talk about, but you had to bring in translations. That’s how I started translating poetry seriously, mostly from Italian, except for one figure, Mohammad Dib, who was from France and somebody I’d gotten to know. I did his book in 1976, then another towards the end of his life. Every year, out of the blue, he would send me his latest title from France. He was an Algerian exile living there.

We exchanged holiday greetings and all of that. At the end he said: “I want to write a book about my trip to Los Angeles in 1974.” This was give-or-take 1999 or 2000. He was there for four months as a regent’s professor. He didn’t have a college degree, but the French Department brought him to UCLA, and I got to be very good friends with him. Together we’d wander around town. I introduced him, he claims, to jazz and jazz clubs. I was 29. He was 54. I’m 6’2. He’s 5’6. It was an odd couple.

Fast forward from all that and we get to 1999. I started a creative writing program and one of its essential aspects was translation; students had to study it. There was a first semester called “The History and Practice of Translation,” and it kicked off with a statement going back to Pound: “Every major change in English poetics is the result of translation.” Quite true. The Lord’s Prayer was translated from Old English—one of the first so-called pieces of English literature. Latin makes three prominent appearances: First around the year 1000; then it enters again just before Shakespeare’s time; finally once more in the 18th century.

In the days of Chaucer, you have French—a heavy influence. Then in the Renaissance you have Latin and Italian. The court language under Queen Elizabeth was Italian, and the sonnet which became so popular, was an Italian form. French again enters with the Restoration, and I think Pound’s point was that translation propels poetic innovation.

Sidenote: When I was in grad school, there was a colleague called Rose whose last name I can’t remember. We were finishing our last year before the dissertation and she said: “You’re writing on Pound. I have 50 of his unpublished letters.” I said: “Hey, get them here, and we’ll put them in special collections.” She brought them in, even though her family wanted to hold on to them. They were her younger sister’s who’d died in her 50s of cancer. She was from Maryland and she had befriended Pound when he was at St. Elizabeth’s. She would write to him and visit him. Wanting to study poetry, she looked up a bunch of famous ones and Ezra Pound was right there near Baltimore—an obvious target. In the first response he said: “Okay, send the poems along—subject, verb, object.” And then after that, he assigns her things to translate because she knew some French from high school or college. Right in the beginning he’s teaching this woman, who’s in her thirties, the art of poetry from scratch, and the key part of it is translation. He says it in his Selected Letters anyways but he also repeats it in these aforementioned ones: “The reason why it’s good for a young poet to translate is because in translation you don’t pick up the mannerism of the poet. You can’t, because it’s a different language. You pick up the approach, subject, and composition, but you don’t pick up the mannerism, which is the worst thing about imitating a poet.”

DG: In your essay “Poetry Interrupted,” you articulated something called “resistance of the self,” a sort of criticism of the ego inherent to lyrical poetry: “If we are to derange the egocentric, expansionist course of U.S. poetry, nothing less is indicated than a resistance to the self, an ideological and aesthetic vulnerability to what surrounds us.” In your view, has contemporary writing in recent years moved towards this resistance or away from it?

PV: Away from it. Completely. After 1974, two years fresh out of grad school and now a journalist, I increasingly witnessed throughout the ‘80s the study of the historical avant-gardes, such as Marinetti. His best manifesto was the 1912 Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature, along with the 1909 Manifesto of Futurism. The others are also important but so off-the-wall. These two are certainly his best. The first rule, Marinetti, says is “destroy the ‘I’ (distruggere il “io” in poesia).” Though my first book was in 1973, long before I’d read that manifesto, I did write a whole collection of poetry called Air and made sure there was no “I” in the poems, which is easy to do in Italian, but not so easy to do in English. In Italian, it’s not necessary to put the “I.”

DG: Indeed, you don’t have to use the pronoun because the subject can be apparent from the conjugation of the verb itself.

PV: When I first came to Italy, I could always tell who was an American because they kept saying “I, I, I—I want this, I want that, I want to go there.” They use the “I” all the time. If you connect this with the proliferation of creative writing programs, a clearer picture begins to emerge: When I started my own in 1999, there were fifty; by the time I retired—if you count the distance learning ones—there were close to 400. I think they’ve done more damage to American poetry than anything. Part of the problem is the formulaic one or two page max workshop poem: “I do this. I do that. I wake up. I feel bad. Whatever.” It doesn’t hold any interest for me, at least in terms of reinventing the language.

DG: We can use this an interesting to Rimbaud, who believed that a derangement of the senses was the key towards poetic illumination. How strong is the correlation between the way Rimbaud used the word “derangement,” and how you use it?

PV: Exactly. I use “derange” because I somewhat break with Rimbaud’s famous letter to his high school teacher. I took it to mean that the senses are the “I.” The ego is a sense. I’m not saying it’s not there—it’s certainly a sense, but for me it’s not an interesting sense around which to create a poem. Ten years later I read Marinetti’s futurist manifesto, but this idea can be found throughout all of his work. We tend to call figures like Marinetti the historical avant-gardes whereas those after WWII were the neo-avant- gardes, but all of them in the end tended to favor Marinetti’s idea of “destroying the ‘I.’”

DG: You edited a posthumous collection of Amiri Baraka’s work, SOS Poems 1961—2013, published in 2014. You wrote in the preface that “along with Ezra Pound,” Baraka is “is one of the most important and least understood American poets of the past century.” Can you talk a bit about the project? What are some of your personal favorite pieces—not just in the anthology, but in general? And do you think writers like Pound and Baraka will ever be “understood,” their genius fully recognized?

PV: Originally I had “misunderstood” but I talked to the Grove editor and we changed it to “least understood.” Still, it’s really “misunderstood,” after all. I remember calling Amiri up five years before having written that. I had done an essay on him and I said: “If I ever do a bigger project, can we start it that way?” And he had just one response: “Cool.” He is very much in the Pound tradition—he himself said so. He hadn’t articulated it much in print, but his work did, especially starting with the first book.

DG: Both are certainly controversial. Baraka is controversial. Pound is controversial—

PV: Oh yeah, and both for the politics—both called anti-Semites, as you know.

DG: Do you think they will ever be understood—their genius fully recognized?

PV: I hope not.

DG: (Laugh.)

PV: Because then they would have to be adopted by—what’s that thing called?—the canon. You heard it here on tape first. Many people I know, not just in the US but also here in Italy, couldn’t be more politically-distanced from Pound, including Pasolini who was on the left. He wasn’t Maoist or anything. Still, for such people, Pound was without a doubt the greatest poet—not just the greatest American poet of the 20th century. And I likewise happen to think so for many reasons, but mostly for what he did in expanding poetic language. In addition, there’s something quite relevant I didn’t say when we were talking about translation but would like to mention now. When they asked Pound: “Why are you so focused on translation?” He responded: “Because I’m looking for a language to think in.” He said that in 1912.

DG: He was ahead of this time. In this respect, I think his genius will become more fully recognized, but in a way where he will remain this “unique” figure, and this is a good thing. Let’s stay with translation and move to Bill Mohr’s question. He wanted to ask the following: “Have you ever translated your own work into Italian? If so, what would be a moment when you found a particular line or image to be difficult to convey into Italian?”

PV: That’s an easy one to answer. I never have. Because I would never translate from English into Italian. Living here, you obviously do it every day, whether verbally, or by means of some some stupid official letter you have to write, which means nothing. They go into some dossier and then you never see them again. But, no. I’ve never translated my work or anybody’s work into Italian. There were plenty of times when somebody was translating my pieces, and because of some confusion they asked for a literal meaning of the stanza. In my terrible Italian, I gave it to them, but the answer is no. However, Bill is on the right track because I think he recalls something I told him forty or fifty years ago: “The other good thing about having a second language—along with Pound’s apropos quote about not imitating someone’s poetic manner—is that when I’m stuck on a poem and I just can’t get anywhere, I’ll translate the piece into my own Italian, and there, often, I see what’s wrong with it. I see the skeleton of the poem. I understand what it’s missing. I understand why, as they say in Italian, it doesn’t stand on its own feet.”

DG: You sort of put a mirror to the poem, but the language is the mirror—

PV: Yeah, I’m able to see why it’s not working. It’s always the question of the poem, not the right word—that just takes time. The real question is why the actual poem is not holding together.

DG: You have this advantage that many poets in the US don’t have—working in another language. Your forte is translating Italian poets, but you’ve not “confined” yourself, as we’ve already said, in this respect. You’ve already touched upon your translation of L.A. Trip by Mohammad Dib was from French to English, and you worked closely with the author to make it happen. How was this project different from the others you undertook, and how did Dib’s reflections about the city ultimately change your own perspectives about LA?

PV: It certainly did. Dib contacted me in 1999 saying: “Hello, how have you been? And so on.” We hadn’t seen each other since 1975, when I went to spend a week with him on the outskirts of Paris—a suburb near Versailles called La-Celle-Saint-Cloud. At the time I had done three French poets, including Dib. His son had email, but Dib never used it. He wrote letters. In one correspondence he said: “I want to write, but I can only do it with you.” I said: “What do you mean?” He responded: “I discovered the city with you and I have these poems. I’ve started writing them but I want you to translate. You send them back to me and I’ll go over them.”

Dib knew English. He had translated English fiction. In 1947, while still living in Tclemsen, Algeria, he published a really interesting essay on American poetics and writing called “The Short Story in Yankee Literature,” which appeared in Forge. He said it’s “a savage literature”—that was his phrase. “It’s a savage country with a savage literature.” He used the word sauvage but he wasn’t putting it down. It’s savage in that it doesn’t have history—and it doesn’t want that. There’s this direct relationship between the object and the writer, which he says is savage. One of my Italian friends, a painter, later said the same thing. I translated my latest piece for him and he remarked: “That’s really interesting. An Italian poet could never write that poem.” I said: “What do you mean?” He responded: “An Italian poet couldn’t just speak directly about a thing. There has to be a mediation. Your language is not mediated.” And so, Dib wanted me to help him mediate all this. That’s how we started. He would send me fifteen or twenty poems at a time—roughly one-page poems, twenty or thirty lines max—and I would translate them, send that back to him via email. His son was working in Paris. He would get the email, print it out, and bring the material to him. Dib would then take it and mark up my translations in red. Afterwards, he sent that back to me. I would then make the corrections we agreed on, which would go back to his son, and they’d collect the manuscript.

When the manuscript was finished, Dib went to his French publisher—and I don’t mind defaming him because I really think he did a disservice to Dib’s work—who actually loved the project. We had set it up so that Douglas Messerli of Sun & Moon Press could publish a joint edition because Dib said the book had to be appear in both languages—French on the left and English on the right. The French publisher in truly stupid contemporary French tradition refused to publish the English—he would just do Dib’s originals, which were in fact created through translation because we would change both versions together. He used my English as a sounding board for his own French. And so, Douglas Messerli said “we’ll just do it ourselves.” In the meantime, Dib dies—suddenly. He got sick in the summer of 2002 while I was on a fishing trip with a friend in Montana. In May of 2003 my wife called me and said: “You know, that friend of yours, Mohammed Dib—he was in the paper today. He died.” And there we were. Messerli said “we’re just going to get it out.” We released it in six months—the whole thing. So now there are two editions of the same book: One as the poet wanted it, and one as … whatever—

DG: The publisher wanted it.

PV: The French publisher wanted it.

DG: (Laugh.)

PV: After he died, his wife wrote me—through the son, of course—a typewritten letter saying: “You don’t know how much consolation he took at the end of his life in those little red pages. She meant the pages he had corrected. She had them all.

DG: That’s an incredible story.

PV: And the book, of course, is called LA Trip—one of the great poems about LA. Yet, for three years I tried getting it reviewed in The LA Times. It did get a review in one place, World Literature Today, a publication that deals with translation, out of the University of Oklahoma.

DG: That shows us the priority of The LA Times, I guess. Let’s continue with another relevant question from Bill Mohr, who says that you you’ve lived as an exile in Los Angeles—

PV: You know why he says that? Because I edited and published a book in 2000 called LA Exile, and it was all poet-writers who came to LA—the youngest arrived when he was fifteen—but all the others came to the city as adults from different states or other parts of the world and wrote in LA; it completely changed their writing.

DG: That’s kind of the opposite of my experience. I left LA and came here, and it’s changed everything.

PV: Right.

DG: But let’s stick with the question, because Bill is right to point out that in some ways, your life has one odd parallel with a very different poet, T.S. Eliot. He writes: “Eliot was about to defend his dissertation when WWI broke out, and so he didn’t get his Phl.D. and become a professor in the United States. You, too, were on the verge of writing your dissertation, but ‘history’ (in quotation marks) intervened. In remaining in Los Angeles, your life’s work as a poet, editor, publisher, and translator has impact an extraordinary number of Southern California poets. If on the other hand, you had finished your Ph.D. and ended up teaching in the Bay Area, where you would have been more at home, how do you imagine your life might have been different? Or are these kinds of fantasies not something you ever think of? Or is that kind of speculation akin to a ‘translation’ of one’s life into a language that has not yet gone beyond the oral stage?” What do you think of Bill’s question?

PV: Not only I, but also people I know keep reminding me of that when I complain about LA. In fact, I would’ve loved to go back to the Bay Area. It’s not the reason I quit. But when you finished your coursework and were writing your dissertation, you’d go on to look for your first academic job. In those days, as now, the same thing happened—no jobs. There was one place in the country where you just didn’t bother with all that in 1972. 250 posted jobs in the MLA for San Francisco. No, 250 posted teaching positions in the Bay Area. Think about those terms today. And you know how many applicants: 58,000. For 250 jobs.

DG: That’s wonderful—in the worst sense.

PV: In the worst sense, yeah, but I did come close to having a job in academe: What happened was that I applied for a Fulbright to teach in Italy for two years. It was very good pay—not from the university or the Fulbright people. There were two trips a year. The host country rented you a two-bedroom apartment for wife and child in Bologna because that was my first choice. I received a letter in December that said: “Be ready to fly on August 31st, but you need to get a physical. You, your wife, and your child. Each has to have one.” I didn’t have the money, so I borrowed it from three people—three physicals for a hundred dollars. After the procedure, I sent it to them.

To this day, however, I’ve never gotten a letter that said you’re not going. They told me: “Get on the plane August 31st. We’ll send you the ticket.” Later, the woman I’d dealt with at USIS (United States Information Service)—who was very kind and supportive throughout the process—kept saying conflicting things: “There’s a hitch in the application. Your papers have gone through. In December there’s a panel in Washington. They meet and select the people. You’re three finalists and two alternates. You’re the number one finalist.” The last part was later confirmed by a guy I met ten years afterwards who was the number two finalist. Like me, he was blocked by the State Department. In those days, your papers went to Europe and they went to State. Now they only go to Europe, or wherever the Fulbright is. Without telling me, the State Department blocked the application because of my anti-war activity as an undergrad. Four years later, in 1976, I used the Freedom of Information Act, and there it was. Oddly enough, it also mentioned somebody from undergrad days: A guy named Al. He was a part of our small group of three or four poets and he turned out to be an FBI agent, which was nice—really reassuring.

DG: That must’ve been a fantastic discovery.

PV: Yeah, it said: “Paul Vangelisti was with …” and then it listed the other three names, but they were blacked out. And so, by simple process of elimination I knew who was who: One guy had died; one guy had gone to Canada; and the only guy left was the one who was still in San Francisco. So that’s the answer to the question but it’s almost a moot point. Right before I was about to go, I had two other job offers: One at Southern Mississippi State, where I wouldn’t have gone, and the other at Bucknell. I told them what I was planning on doing and they said: “Okay. If you send the documentation, we’ll wait until you come back. And then we’ll make you the same offer. So, whether you’re done in year or two years, it’ll be the same offer.” I said: “Great, I’m really interested in this.” And then three or four months later, it didn’t matter. I got my department at USC to give me one more year of an assistantship—and the rest is history. The academic career, in a sense, was over quickly.

DG: There was a silver lining there. Would you say?

PV: Maybe. In May of 1972 I was driving a taxi. I still remember Founder’s Hall, where the English Department was. That’s where I walked out. I didn’t finish my dissertation. It was maybe half-written. The first sixty pages were published a year before in The Southern Review, and this is important. That was through Davie. I backed up on a Saturday, filled up a couple boxes with books from my office, put them in the trunk of my cab, and that was the end of my academic career. I drove off with the yellow cab. Then I became a journalist.

DG: You’ve done well for yourself.

PV: I’ve thought more than once about where my poetry would’ve gone—more than once, but there was a reason I quit.

DG: Let’s continue with another question from Bill questions and it’s the following: “Have you ever read a translation of your work that you particularly admire? Or has there ever been a moment of disagreement that couldn’t be resolved with the translator?”

PV: I’ve published seven or eight books in Italy so I have a lot of translated work. I absolutely admire two—both by great Italian poets, one gone and the other still with us. Giulia Niccolai, who left us a year ago, did two or three books and we always did them together. In a literary sense, she is the most bilingual person I know—bilingual in the best spirit of the word. I have to say this in the interview: There are poems she wrote, some are both in English and Italian, and she has one line that she repeats over and over in her work. It’s a line of prose: “Even poetry lies on the page.” She says this in English because that’s impossible to say in Italian. Untranslatable. English captures the two meanings of “lie” and I can’t think of a word in any other language that has those two meanings—certainly not European languages. I’ve translated lots of her work.

In addition, there are Adriano Spatola and Corrado Costa—though I remember Giulia’s presence because neither of them could speak English. They did one book of poems which was really good. And then there’s my long-time friend and collaborator, Andrea Borsari, professor of aesthetics at the University of Bologna, who has collaborated on a host of project since the turn of the century. More recently, there’s Nanni Cagnone, who’s another fine poet. He’s still with us at 82 and did a very good translation of sonnets in 2015. In working with him numerous times, I read unpublished poems he’d written—they were going to be bilingual editions—and during the course of our collaboration I changed the original more than once.

DG: So your experience has been good overall.

PV: Good. With one or two exceptions. And I should mention the book I showed you by Millie Graffi—Six White Mules. Excellent translation. And that one I didn’t change anything in the English. That was the only publication of that poem.

DG: Let’s have a look at Bill’s final question, which is the following: “Is there an inherent theatricality in translation, in which the actor’s approach must be closer to a Brechtian distancing/alienation rather than some variant of «method» acting?” A short but tough one.

PV: I get the method acting part, but I don’t exactly get—do you know what he means by Brechtian distance?

DG: I think what he’s talking about is not conjuring up some concrete event in your life, but instead drawing upon an archetype, a theory, or concept—something other than yourself. A sort of distance from your own psyche and emotions influencing your artistic portrayal of different emotions. For example, if you want to portray sadness, you don’t go directly to your own personal experience but channel the personal experience of the world in general.

PV: Yeah, that’s a really tough question but he’s right about that. It’s not a “method,” and it’s not even acting—that isn’t very important for me in translation. I think what’s more important is trying to figure out where you sit in your language and where the poet you’re translating sits in his or hers. And then trying to approximate that place back into your language.

DG: I think that’s a perfect answer. Indeed, not an easy question to answer because the translator must both draw from the experiences of his language in general, but also of the language he’s receiving—

PV: Let me put it this way—if we go back to Pound, we’re faced with the question he was asked: “Why do you translate?” Again, his response: “To find a language I can think in.” And this allows us to address the inquiry of why he experimented, mainly because translation is a natural part of that. He said this way at the beginning, in 1912. He didn’t have it figured out at that point but translation became one of the ways he did that. But the other thing about Poundian translation, which I’ve come to appreciate as I’ve gotten older, is that he translated to bring values that did not exist in American literature from another language. “Values”—that’s the word he used. It’s the best one, I think—not themes, not styles, but values. Poetic values in poetic language.

DG: For a long time, you’ve been Chair of the MFA program at Otis—

PV: I was the chair.

DG: Ah, you were—

PV: I’m gone. The program’s gone.

DG: This I didn’t know.

PV: Oh, yeah. The program was canned in 2020, officially in 2019—

DG: Well, that shows you my awareness of what’s going on in the home country.

PV: I retired in 2018. I had started the program in 1999. I stepped down in the fall of 2015 as chair and went on phased retirement—Bill’s on the same thing. At Otis, you stepped down from being chair in the first year, but you got full professor’s pay. In the second year, you did half-time and you got sixty percent pay—that was really good. In the third year, you retired. So I did that. I started the process in the 2015/2016 academic year and by 2018 I was retired. Now I’m Professor Emeritus and though I still belong to the school, I can’t put a department under my name. The man who took over for me—someone who I’d originally hired, along with several other people, all of whom I’d hired—destroyed the program, to put it bluntly. They were essentially encouraged by the administration to do it, something they then succeeded in doing. The last students were admitted in 2020 and the last student got his MFA in 2022. There’s no more program there and when that happened—which would’ve been a year ago spring—I got so many emails from former students saying: We feel so betrayed by this.

DG: My God.

PV: Yeah, I don’t want to go into great detail. Suffice it to say, the program as we conceived it in the beginning—particularly I and Dennis Phillips, who taught poetry in our program—was supposed to be in Dennis’s phrase the “anti-MFA MFA.” We tried to do everything MFA programs didn’t do, all of which has been adapted now: heavy literature component, translation, which nobody was doing, history and practice of books, book art—that was required in the program. They got rid of all that. The faculty overruled me, and at the end they got rid of the program.

DG: It’s sad to hear this. Let’s talk more about the curriculum. You must’ve assigned a fair amount of international writers and translation.

PV: Yeah, it was a required course. I’ll give you an example. On the whole, we had four classes per semester, and we had five of those. The last semester was four units—the thesis all by itself. In a typical semester you had two lit classes, then for one or two credits there was a visiting writers section (seven per semester); those who came gave a lecture, answered questions, and hung out that day—from all over the country, all over the world, really.

We had a French writer who came through. We didn’t fly him in, but the French cultural services handled it, just to give you an example. The same happened with Italian or Spanish writers. In addition to all that, there was one workshop class, which was on the last day of the week. The first two days of the week were the lit courses; Wednesday night was a visiting writer; and, finally, we had the workshop divided into fiction/poetry—two cohorts per discipline. All that got wiped out when I was still there in 2015. In the last year I taught there, the guy I’d hired who later became chair decided to have two workshops, like always, but with poets and prose writers together in both. The poets went ballistic because the critical response to their work was always: “Oh yeah, you know I don’t read poetry but this is kind of interesting.” The fiction writers, on the other hand, loved the poets in the cohort because somebody would finally talk about the language and the line edits—they never talked about that in the fiction workshop. What they did was discuss character, plot, and all that. So it was a disaster. People complained all the way through that year. Two of us taught the workshop—a fiction writer and poet.

DG: Lots of happy news there.

PV: Bill taught a lit course twice in the program. Once it was half and half with an LA-writer, Norman Klein. He was what we’d call an intellectual historian. One magnificent book I’d recommend to everybody interested in LA is Los Angeles: The History of Forgetting. It’s been translated into other languages. Indeed, that’s what we’ve learned to do in LA is forgetting.

Another time, Bill taught a course alone. I had this so-called studio model, or academy model taken from the old-fashioned versions of art schools, where you have a core faculty of eight people, and every year they teach a one semester course then rotate, which I also thought was great, but they got rid of that too.

DG: It seems like all good things from the past are replaced with modern, inferior versions which don’t work as well.

PV: Yeah, on the whole the narrative is usually as follows: “There are two writing courses and one literature course but you don’t really have to do literature, blah, blah, blah, because who needs literature in a writing program?” And that’s that.

DG: Let’s return to Italy and discuss your 1991 work, Villa, set in Ancient Rome. Scholars such as Bill Mohr have written—with regard to your work—about the connection between the glory of Rome and American power: “it has a laconic and poignant irony that makes it seem as though it might just as well be set in Los Angeles: ‘modern’ Rome, in the early period of its empire, and postmodern Los Angeles provide the same predicaments for their citizens.” Indeed, American militarism and expansion have come to a grinding halt, and it seems we have entered a Roman style age of decline. Were you already thinking along these lines in 1991, and how have your views changed?

PV: It was a version of post-modern history; I said before that I’m not crazy about all that, but it was. I started the poem in 1983 and finished it in ’86. It was published five years later. It’s a complicated work. There are letters from a non-existent courtier at Hadrian’s court; letters to different friends—all real but with Latin names.

When we read the poem at Beyond Baroque in 1986 all the friends who were poets, fiction writers, and artists presented their own section—the section to the person I was writing the letter to. And so, I didn’t read any of it, except the introduction, which was made up through another friend—a philologist in Romance languages at UCLA. Together we created the translation of the preface, which was only a page but nevertheless complicated.

He had looked at Suetonius, who was a character too. We studied Robert Graves’s translations and he as a linguist said: “This is adverbially inclined. If you’d read the Latin …” I couldn’t read Latin that well.

So this was a work which I would truly define as collage, synthetic, but not collage in the conventional sense—it was right at the height of the first post-modernism boom. It was also right after the building of LA’s Getty Villa; and though it wasn’t modeled after Hadrian’s, its roots are undoubtedly Roman— the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum. Moreover, The Getty Center had just published a book on Hadrian’s Villa, so it was really in the air. I thus saw LA as the furthest reaches of the Empire in the purest sense of grand decadence. And that’s really the theme of the book. At the end, Hadrian dies and the reading is over. It ends with him saddling his horse for the next day so he can split and go back to the other side of the Apennine—to where we’re sitting today, in Northern Italy, where his mother came from and where my mother also comes from. That’s the whole parallel personalism.

DG: You stitched the fabric together well and the air was ripe for it.

PV: There was an attempt in the writing of it to come up with Latin-sounding meters. And though there’s no strict meter, I did run it by a friend, Peter Whigham, who was a translator of Catellus. He had done the Penguin edition for his poems (first published by UCLA Press). He left us a year after my work was finished. He had told me: “Yes, you got that. I read it out. You got the Latin.”

He was a Brit, so he went to public school. Then, like any gentleman, he dropped out of Cambridge after the first year and became sort of a remittance man wandering around the world. He found himself teaching at UC Santa Barbara, then at Berkeley, but he taught translation at both places and told me that’s the way it should sound if it were written—and it’s not written—in Latin. And if LA was the end of the Empire. And if if if if ….

I did three books of verse fiction. Villa is the first one, and there are two others.

DG: Let’s segway into a problem we have today. In a video conversation with Neeli Cherkovski, and Charles Bernstein, you talk about how the confinement of the pandemic affected you, stating how basically the kitchen, living room, and bathroom became your “horizon for over a year.”

PV: I’ve been thinking about that these last two or three months. I came to Italy on April 28th and wasted two or three weeks trying to finalize all these documents to get my citizenship. Then on May 1st they dropped the mask mandates. When I first arrived to this hotel for two days, I’d wear a mask to the breakfast room. Later we couldn’t even get up and get our own buffet. We had to sit there with our FFP2s on and wait to be served. You would take it off to eat. Then all of that went out the window a couple days later. We could get up and walk, and so on. All this was very much on my mind, so I’ll give you a personal answer—and more importantly the poetic answer (all in the spirit of keeping that self down). The personal answer is how you put it a few minutes back—my horizons suddenly changed. Everyone’s horizons sort of disappeared. To paraphrase Thoreau: He traveled extensively in Pasadena.

DG: (Laugh.)

PV: Remember that one? Emerson was interested in Vietnamese poetry and so on. He asked Thoreau: “You’re not traveling?” Thoreau responded: “No, I travel extensively in Concord.” So that was a factor, but also on a more personal level: What happened is that I just got more and more confused as the world got more and more reduced. And by now you must know that what I’m least interested in—the self—started taking over center stage. Because there was nothing else. The outside wasn’t there. That’s what happened on the personal level. At the same time, I started writing every day. I was keeping a journal, a chronicle of my thoughts on different subjects, my outrages with Trump, whatever.

But, unlike other poets, I couldn’t write poetry. Two of my friends explained it in different ways. One of them had done twelve years of psychoanalysis and he said: “You’re the only person I know whose unconscious is in the external world.” Meanwhile, the other person stated: “You’re the only person I know who doesn’t write from one’s life but lives from one’s writing.” That’s to say, I write about it first in a poem and then I unfortunately live it—a month later, six months later, whatever. So, thinking about all that in relation to the pandemic, things got really scrambled. It felt as if I couldn’t write, though I wrote every day. All I did was read and write. I would read eight to ten hours and write for about two or three. I’d sleep six or seven hours.

In the end, something did happen, however: All metaphors, statements, and lines tended to disappear. Everything got—I don’t want to say literal, but fragmented, condensed. So I wrote something which is coming out in Italy this fall. Fragment Sides. It’s all fragments. The stuff in this series is about 18-20 sections, consisting of roughly the same amount of pages—one per page. Some are as short as three lines and some are as long as six or eight, but that’s it. In this piece what’s most important is the thing that’s not said—in the fragment, in the white space. I’ve never written that way. For me this was a direct result of how I felt. The so-called advanced state—the first six months after the pandemic.

DG: This directly relates to what we were talking about earlier: Is it the individual who makes the surroundings or does the environment make the individual? Your testament seems to be concrete proof that the environment has a huge effect. The environment makes the writer. No matter how much you try to emphasize the “I,” which is what many poets do, it’s really the environment that creates it.

PV: In this piece I use the “I” two or three times because then I really mean something. For once I’m working inside out, which is a total first for me. At the end, apart from Pound, it’s a curious variation on one of my biggest influences, Jack Spicer: In his Collected Books—not collected poems—there’s a big afterword by one of his friends and contemporaries, Robin Blaser, who calls Spicer’s work “the practice of the outside.” He’s saying it comes from the outside in. And what happens during a pandemic? There’s nothing coming in from the outside. We can’t quite say it’s nothing, but it’s fragmentation.

DG: This whole notion of the “I” seems to be a phenomenon of the young poet. Do you think it could be useful for them—at least for their first book or so—to go down that road? To write with the “I” and sort of purge that from the system?

PV: I think it is if they understand they’re doing it. If they do understand, it could be a step towards confronting the “I” to try and see if there’s another way to articulate the same thing. That’s a vague answer, but what I’m attempting to get at is this: If poets are trying to purge it, I think it’s a good idea. If, on the other hand, they think that to develop creatively they have to develop their personality—something many poets believe and do—it’s tragic. I could care less about anyone’s personality, let alone the poet’s, unless it’s a person with whom I have a romantic or familial relationship. But what I’ve said really concerns everything. If you’re aware of what you’re doing, it shouldn’t stop you from doing it, but you should know what you’re embarking on in the process—only then can you decide what the next step will be. Finish it. You know those classic creative writing cliches: Follow your madness all the way out to the end and then look at it. Don’t try to develop some sort of equilibrium while you’re working. Try to reach the end and then see what you’ve done. But you have to be ready to throw out the result. Not just that. You have to be ready to throw out the whole book.

Author Bio:

Paul Vangelisti is the author of more than thirty books of poetry, as well as being a noted translator from Italian. Recently his sonnet sequence Imperfect Music was published in a limited, bilingual edition by Galleria Mazzoli Editore in Modena. In 2015 he edited for Grove Press, Amiri Baraka’s posthumous collected poems, S.O.S.: Poems, 1961-2014. In 2006, Lucia Re’s and his translation of Amelia Rosselli’s War Variations won both the Premio Flaiano in Italy and the PEN-USA Award for Translation. In 2010, his translation of Adriano Spatola’s The Position of Things: Collected Poems, 1961-1992 won an Academy of American Poets Prize. He lives in Pasadena (California) and Bagnone (Italy).